|

|

but taken literally (after all, the doctrine of transubstantiation affirms that one miraculously and literally swallows the leader during the Eucharist.) To the Mexica, death was a beginning, not an end, and seems to have been closely allied with an agrarian sensibility—or, at least, with one tied to close observation of the natural world and awareness of the specific ecology in which they lived.

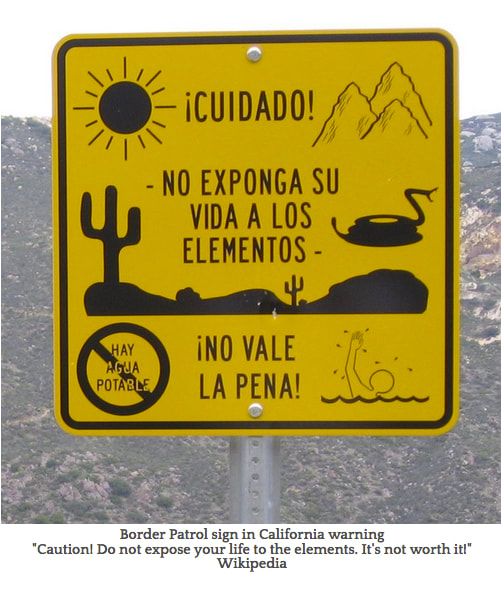

We have here the problem of culture. Herrera, in interview in 2015 [2], says that he actually did quite a bit of research into Mexica myth for Señales/Signs, "for the purpose of giving me a structure, and giving me particular symbols to use, and giving me certain features of several characters...but I have to say that my purpose was to write a novel in which it was not necessary for the reader to know all these other things." If Herrera hoped to defoliate the story and allow it to stand bare and miraculously alive, he may have succeeded even better than he anticipated. However, that Mexican Herrera's fine novel could exist apart from its roots seems unlikely. Indeed, when this norteamericana read it for the first time, in English, knowing casi nada about what fed its structures, I got the feeling of smooth, exquisitely crafted language, but perhaps a tale extracting energy from the lives of what snootily used to be called "the underclass." Caveat: a) my first impressions are often wrong, and b) I fear for the reader enjoined to take nothing else but first impressions from the book and, god help us, seeking to copy it. It offers so much more. What I am suggesting is that, yes, as Herrara insists, ...it’s not a re-creation of the myth; I’m using that myth as a found object. I take it, and I put it in this other context, in this other time, in this other situation, and let it do its thing. But I’m not trying to revive it. Nor are we trying to revive a corpse. Metaphoric language, analogy or even fable such as may even appear in Herrera's much admired medieval literature is not an invitation to solve a math problem. Metaphor resonates—does "its thing," if you will—but one of the "things" it does is connect the reader and writer to culture, to words and ideas that are more than what they seem, more than semantics, perhaps in part because of the subliminal cultural messages they carry. Indeed, it has often been said that language carries culture; and I would emphasize that metaphoric language does so in spades. Further, one's culture is not something one puts on like a new suit. In fact, it is not external to us at all, though what it creates is all around us. It saturates and enlivens our mother tongue. It is in the drinking water. It "does its thing" in one's creations despite all efforts to the contrary; and if, as Herrera says, the reader "could feel the density of that"—the "that" being his selection of mythic elements, freighted even with the unintended/uninvited stowaways that hitch a ride on his words—his words have successfully flown the nest, all grownup and fending for themselves. That is, they go beyond even their author. What I am also finding as I consider Señales/Signs, part of an accidental trilogy, is how it challenges the work of constructing a novel when the writer does not walk through the process eyes closed. In considering the Russian Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky's Memories of the Future for another journal, I wrote of the unreliable character on a tether, struggling to escape the confines of a fictional world and the dictates of its author. This theme carried over to Felipe Alfau's Locos, whose characters are also an unruly lot. Ostensibly, Herrera's characters have a different purpose; they are more constrained by this purpose and, in spite of their author's best efforts, the cultural baggage they carry. At the same time, neither Herrera nor the previously mentioned Krzhizhanovsky is god: as I hinted above, if a writer does their job, writers cannot have absolute control over the material or the characters who put flesh on the narrative. As serious readers, we will always find something more; it is our pleasure, what keeps us glued to the literary page, and we are not always off the mark. Further, though Herrera insists that a reader does not need to "to go and look up these things," but simply feel their density— perhaps not in the middle of reading the novel, but if my curiosity is challenged, why not?—it will certainly do no harm. I did, in fact. I then reread the book (it is certainly short enough); and like Makina, its central figure, I felt as though I descended another level, or more, when doing so. Makina has been called a "Mexican Orpheus" by Aaron Bady of The Nation, but I am not sure that is accurate. Readers might need to be reminded that the mythos in Herrera's rendering is not a derrivative of what the West believes Orpheus of the Greek myth was, looking for his/her dead lover. While there is no doubt that some very crass Europeans damaged it, the mythos of indigenous Americas is not so impoverished as to be justified, propped up by the West's tired claims to antique Greek culture. First of all, the cognate here is a woman crossing the border between Mexico and former Mexican territories seized in the Mexican-American War (aka "La Guerra Defensa," in Español.) That territory is now cast as Mictlán, the land of the dead where the common people go—i.e., the USA. As far as I remember, no such political critique, even an oblique one, can be found in the Greek myth of Orpheus, whereas we would be incredibly dense to ignore it here. Entonces, in Chapter 8, "The Snake that Lies in Wait/La serpiente que aguarda," we read the epitome of Anglo perjuicio/prejudice—those unfounded fears that bump them in the night, projected upon their Mexican neighbors: Nosotros somos los culpables de esta destrucíon, los que no hablamos su lengua ni sabemos estar en silencio. Los que no llegamos en barco, los que ensuciamos de polvo sus portales, los que rompemos sus alambradas. Los que venimos a quitarles el trabajo, los que aspiramos a limpiar su mierda, los que anhelamos trabajar a deshoras. Los que llenamos de olor a comida sus calles tan limpieas, los que ls trajimos violencia que no conocísn, los que transportamos sus remedios, los que mereceremos ser amarrados del cello y de los pies; nostoros, a los que no nos importa morir por ustedes, ¿cómo podía ser otro modo? Los que quién save qué aguardamos. Nosotros los oscuros, los chaparros, los grasientos, los mustios, los obesos, los anémicos. Nosotros, los bárbaros. We are to blame for this destruction, we who don't speak your tongue and don't know how to keep quiet either. We who didn't come by boat, who dirty up your doorsteps with our dust, who break your barbed wire. We who came to take your jobs, who dream of wiping your shit, who work all hours. We who fill your shiny clean streets with the smell of food, who brought you violence you'd never known, who deliver your dope, who deserve to be chained by neck and feet. We who are happy to die for you, what else could we do? We, the ones who are waiting for who knows what. We, the dark, the short, the greasy, the shifty, the fat, the anemic. We the barbarians. We, the embodiment of all that Anglos abhor and fear in themselves. Which is, by the way, why I fear the casual reader who wishes to imitate as good a work as Herrera's, lulled by its skillfulness, thinking that by writing about what he or she conceives to be "lowlife," or grunge, they are at the cutting edge of contemporary writing. Dig deeper. Pay your dues. Do your homework. Secondly, non-Orphean Makina, whom Herrera suggests could thus be called a "border character," is asked to go search, not for her lover, but for her brother, desaparecido after crossing over the frontier. Her ambiance is smarmy, though not narco-mundo-ish, with a lot of tough talk that has been compared by some reviewers to those in the novels of Chandler, Hammett, and Mosely, whose novels Herrera also admits to having enjoyed. As I have said, the mythic material undergirding this is the analogy of a trip to the land of the ordinary dead, Mictlán; and it was, to quote Herrera, …the place where most people went after they died…. There were two rulers, though that was really one ruler, because— with this people— all the gods were at the same time two gods, feminine and masculine. There would be a feminine and masculine part of the same god, for example, the two rulers as the two versions of the one god of the dead. In order to get there, you would have to go through nine underworlds. In each one of these underworlds, you would have to face a challenge. Nobody knows the exact meanings of these challenges, because this is a world that disappeared, that was destroyed by the Spaniards. We only have a general understanding, not very precise. But we do understand that with each underworld that you cross, you are getting rid of some part of you, some part that makes you a living human being. And when you get to the last underworld, there is only silence; no others and no sounds and no life. Chapter 1 of Señales/Signs, "La Tierra/Earth" begins with the phrase, "Estoy muerta/I'm dead," and with the earth collapsing around Makina, a sinkhole that nearly takes her down with it. The intricacies of using the Spanish verbs, estar as opposed to ser, tell us that the opening line is a play on words: estoy indicates a temporary state; whereas the phrase would have to be "Soy una muerta," if she were actually a dead person, a ghost. But we get the hint. Each succeeding chapter corresponds to the name of the "underworld" she enters—"El pasadero del agua/The Water Crossing", "El lugar donde se encuentran los cerros/The Place Where the Hills Meet," "El cerro de obsidiana/The Obsidian Mound," etc. For those wanting high definition, FYI, the challenges Herrera refers to are supposed to take four years to perform; but then, as I have said before, a work of fiction is not a math problem, and Herrera graciously spares us the mechanical approach. Looking over what the author has said, though, I confess I do think of the physicists' "Arrow of Time," whereby, per inertia, change does not work in reverse and, thus, even the entire universe will eventually end and what follows will be a resounding, eternal silence. Oh, dear. Now, in Mexica mythos, souls were of varying types. Some souls could leave the body and return. When such a soul did not, that was the individual's death; and upon that death, such souls would dissipate and travel to the world of the dead. But let's dispense with the woo-woo: as Herrara says, That place is the place of re-creation. In this world, you didn’t die and disappear, and you weren’t reincarnated: You came to this place of silence to somehow be part of a re-creation. In fact, according to a number of indigenous myths, this world is not the first. In Mexica myth, the next world is the World of the 5th Sun. All those souls, deaths, in a sense are spiritual compost. In terms of the novel's construction, however, our author is not—most assuredly not—retracing Mexica steps to recreate a set of beliefs or a body of ancient lore. As Herrera himself has said, "…I wasn’t trying to tell you about the Mexica culture. I just used it, I took it, and then I did whatever I wanted with it." To which I must add that "it," tiptoed out of the author's back yard and did whatever it wanted with the reader, subliminally letting its shadow fall over his or her shoulder. The hope of my immigrant ancestors, as they were limited in experience and, perhaps, vision, was to recreate as much of their old world as possible with the important exception of specific improvements in their economic situation, in freedom from persecution, and a brighter future for themselves and their children. I don't see much difference between the aspirations of those old Quakers and the aspirations of any Mexican or other immigrant coming to the US, save the urgency of those who are fleeing a war zone—re-creation. But, in their innocence, the believer in what one acquaintance sarcastically called, "geographical salvation," a better life elsewhere, does not, cannot, know what the actual experience will entail. Unlike the certainty of myth or spiritual belief, both matters of irrational conviction, the world of the dead may actually be lethal. However many trials, the passage to and through the underworld— might I suggest the world of state-supported ignorance that the US has officially become?— may kill you. [1] In English, Signs Preceding the End of the World, trans. Lisa Dillman. And Other Stories: March 10, 2015. En Español, Signs Preceding the End of the World. Editorial Periférica: 2010. [2]Further quotes of Herrera's drawn from an interview of the author by Aaron Bady, "Border Characters," in The Nation, https://www.thenation.com/article/border-characters/, accessed 10/1/17. |

Afterword:

Dia de los Muertes Figure.

Wikipedia

A great deal of discussion re: translation has gone into Herrera's use of "jarchar," which Lisa Dillman has translated as "verse." Now here is a writing technique, pardon the expression, with balls. Herrera has said that "jarchar" is part of a poem from the middle ages, in Spain, written in what I would call aljamiado (Arabic characters used to write in the Spanish of the day.) The voice, Herrara claims, is often that of a female saying goodbye; and was often the last part of a poem. It carried the implication of transition, having a foot in two worlds, and so on. The author notes,

For me, this novel is about a character, Makina, who is in transition, who is moving in

between countries, who is moving between languages, who is moving between

identities.

It was really just an intuition. I decided that I wanted to use it [jarchar,] without any

explanation, and that I would use it very loosely, as a synonym for going out, going

between one place and another.

Presumably Herrera is no Mexican Humpty Dumpty, arbitrarily making up the meaning of a word when it signifies something else entirely:

In Spain people sometimes ask me if it’s a word that comes from some language in

Mexico. In Mexico, they ask if I got the word from a Spanish text. This is part of what I

wanted: to create some strangeness, to open some space for the reader to resignify the

text in his or her own terms.

And Dillman, his translator, brilliantly chose "verse" as the word that, yes, carries the notion of transition, exiting, movement from y to z but is just strange enough to nip at the reader's heels urging them onwards. On the level of language, it is remarkable as a writer's specific technique.

Yes, I like to think that when we say, "Remarkable Reads," one of the elements which catches our attention in a work is what it means for those of us who are writers. I have, as a consequence, woven in much of what I think about that into the essay above. In addition to very careful attention to The Word, I also believe that Herrera himself offers wise council/consejo about using lore from one's culture's past. No self-respecting metaphor, analogy, symbol, icon, etc. can be used as a free-standing prop, let alone interior decoration: move it arbitrarily into the limelight and it will burn your fingers off. Turn it into a traffic cop to arbitrarily to direct the narrative in your tale, and you will wind up in a literary ditch. Like a beacon, perhaps a foghorn offshore, intermittently sounding its warnings in basso profundo, it had best be something that resonates with both writer and reader, a stowaway (even Herrera uses that word) like Joseph Conrad's Secret Sharer rather than a prescriptive device taken off the literary discount counter.

For me, this novel is about a character, Makina, who is in transition, who is moving in

between countries, who is moving between languages, who is moving between

identities.

It was really just an intuition. I decided that I wanted to use it [jarchar,] without any

explanation, and that I would use it very loosely, as a synonym for going out, going

between one place and another.

Presumably Herrera is no Mexican Humpty Dumpty, arbitrarily making up the meaning of a word when it signifies something else entirely:

In Spain people sometimes ask me if it’s a word that comes from some language in

Mexico. In Mexico, they ask if I got the word from a Spanish text. This is part of what I

wanted: to create some strangeness, to open some space for the reader to resignify the

text in his or her own terms.

And Dillman, his translator, brilliantly chose "verse" as the word that, yes, carries the notion of transition, exiting, movement from y to z but is just strange enough to nip at the reader's heels urging them onwards. On the level of language, it is remarkable as a writer's specific technique.

Yes, I like to think that when we say, "Remarkable Reads," one of the elements which catches our attention in a work is what it means for those of us who are writers. I have, as a consequence, woven in much of what I think about that into the essay above. In addition to very careful attention to The Word, I also believe that Herrera himself offers wise council/consejo about using lore from one's culture's past. No self-respecting metaphor, analogy, symbol, icon, etc. can be used as a free-standing prop, let alone interior decoration: move it arbitrarily into the limelight and it will burn your fingers off. Turn it into a traffic cop to arbitrarily to direct the narrative in your tale, and you will wind up in a literary ditch. Like a beacon, perhaps a foghorn offshore, intermittently sounding its warnings in basso profundo, it had best be something that resonates with both writer and reader, a stowaway (even Herrera uses that word) like Joseph Conrad's Secret Sharer rather than a prescriptive device taken off the literary discount counter.